Ammonia is a pivotal energy vector in the ongoing global energy transition, serving as a versatile feedstock and a prospective low-carbon fuel for diverse applications, including electricity, maritime transport, reliable storage and transport medium for low-carbon hydrogen (IEA, 2021; IRENA, 2022). Further, ammonia benefits from an established global market and relatively mature infrastructure. Yet, ammonia accounts for 3% of global CO2 emissions, with a carbon intensity that outpaces even steel and cement (IEA, 2021; Smith et al., 2020). The prevailing ammonia production (AP) pathway, reliant on steam methane reforming (SMR) and the Haber-Bosch (HB) process, is predominantly fossil-fuel-based (natural gas and coal) (Salmon et al., 2021). However, its decarbonization remains a formidable challenge, necessitating technological and policy interventions to mitigate its environmental impact.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) offers subsidies to scale up low-carbon energy technologies in the United States. This paper evaluates the economic impacts of the IRA on low-carbon ammonia production (LCAP) technologies, focusing on technology, policy, and market uncertainties. We use a stochastic Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model to assess the IRA’s financial provisions for LCAP: conventional SMR, SMR with Carbon Capture System (CCS), indirect biomass gasification coupled with SMR (BH2S), and Alkaline Electrolysis (AEC).

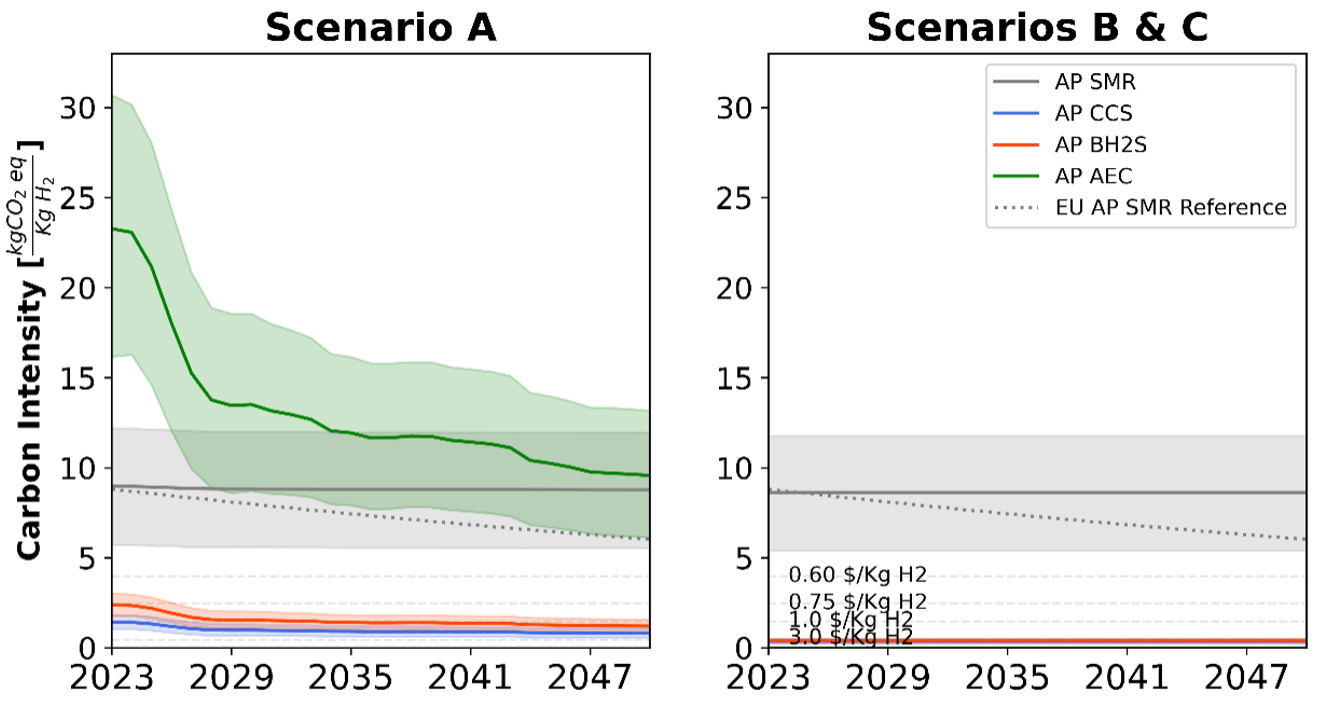

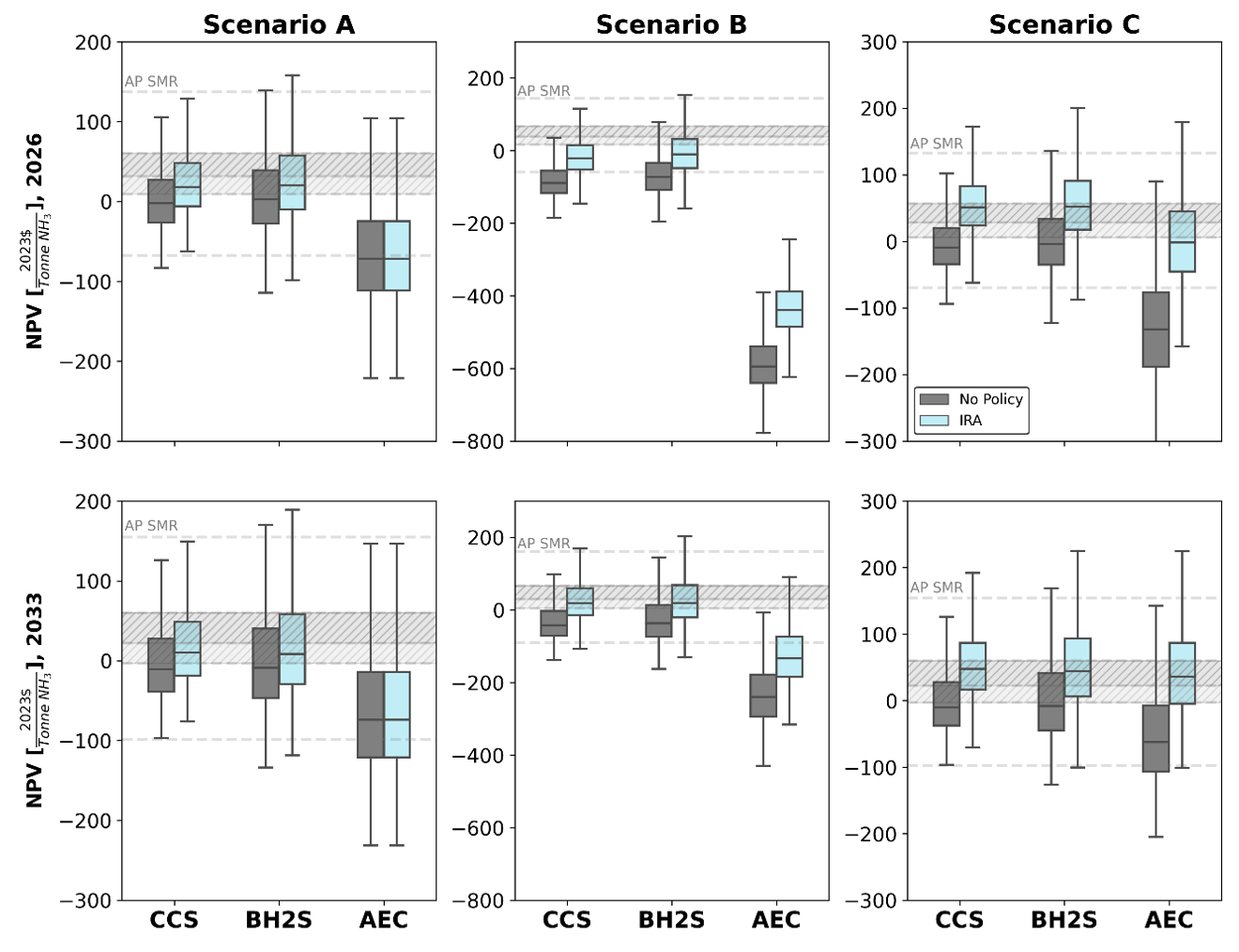

Our modeling results highlight that the successful deployment of LCAP under the IRA depends on the lifecycle carbon intensity (CI) of not just feedstock (natural gas and biomass) but also, crucially, electricity (Figure 1). The IRA framework does not reward (enough) LCAP technologies connected to the US power grid (Scenario A) – although expected to decarbonize significantly under the IRA, the grid is still carbon-intensive to the extent that the subsidies are not matched with the marginal cost of reducing carbon emissions through LCAP, making the incumbent technology – SMR – always economically a better choice for investors (Figure 2). This conclusion holds under two time periods analyzed – 2026 and 2033 – to account for technology improvements and cost reductions. It holds across thousands of Monte Carlo simulations covering critical variables that determine the economics of these technologies.

Figure 1. Carbon intensity of AP technologies: grid versus hybrid wind farm

Then, the critical question the research answers is under what conditions the IRA will likely stimulate the deployment of LCAP. We find that only when LCAP’s electricity consumption is carbon-free will we likely witness their economics outperform the SMR’s. We distinguish between a vertically integrated business model where an AP investor would build and own an off-grid hybrid wind farm (Scenario B) and a case when the investor signs a long-term power purchase agreement (PPA) with the hybrid wind farm (Scenario C).

Our results show that only under the PPA do the economics of CCS and BH2S outperform SMR in almost all the simulations and years considered. Albeit consuming electricity with zero carbon emissions, the subsidies are insufficient to justify the upfront capital expenditure (capex) for AP investors to build and own the off-grid hybrid wind farm because the near-term cash flow highly influences the Net Present Value (NPV). The build-and-own business model is incredibly unattractive for AEC because of the higher electricity requirement, hence capex, than the other two pathways – CCS and BH2S.

AEC economics heavily depends not just on subsidies but crucially on wind and electrolysis cost reductions. In the near term (2026), AEC will be unlikely to deliver higher NPV (than SMR) in all configurations considered. Only, in 2033, AEC, with IRA subsidies and under the PPA arrangement, offers a 50% higher return (median NPV) than SMR. Most of AEC’s economic improvements between 2026-33 are in cost reduction and wind resource improvements. However, CCS and BH2S pathways offer higher NPV (relative to SMR) than the AEC pathway in the near (2026) and medium term (2033). CCS and BH2S offer 60-90% higher economic returns than SMR, outpacing the AEC pathway not just in 2033 but in the near term.

The improvement in AEC’s economics due to technology improvements and cost reductions depends on investor participation in early deployment to drive these costs down. If the policy concerns early AEC deployment to drive costs down, IRA subsidies may need to be increased to account for these dynamics (i.e., the $3/kgH2 tranche increased to $4.8/kg). While public attention was focused on the trade-off between the stringency of carbon accounting of the AEC pathway and its early deployment, irrespective of these cost reductions, AEC still underperforms relative to CCS and BH2S in the IRA policy timeline. Thus, technology neutrality in designing policy support for low-carbon technologies is essential. At the same time, the focus should be on stimulating innovation in low-carbon hydrogen technologies and, crucially, their supply chains and market organizations, such as the 24/7 clean PPA market.

Figure 2. NPV of low-carbon AP technologies

The IRA provides unprecedented support for AEC, but the technology underperforms from private and public perspectives: its NPV is lower than those of CCS and BH2S, while its carbon abatement cost (CAC), in most cases, exceeds the social cost of carbon and that of CCS and BH2S. Although marginally exceeding the recent EU carbon prices, IRA subsidy programs are cost-effective in terms of value for public money in supporting hydrogen-based climate mitigation technologies.

It is essential to consider nuances of the US tax credit markets because tax credits under the IRA will not translate into subsidies on a parity level. Thus, the levelized cost approach should explicitly consider these transaction costs. Ignoring the complexity of the tax credit market and its interactions with the PPA markets will result in an underestimation of LCAP levelized cost, especially those with significant barriers to deployment and demonstrate their efficiency at scale (Abolhosseini & Heshmati, 2014; Barradale, 2010; Kahn, 1996). Risky and unproven (at scale) technologies (AEC has the highest risk profile) will involve higher capital costs and verification, compliance, and monitoring costs, potentially significantly increasing transaction costs beyond what this study assumes. Technologies with high-risk profiles will be costlier for the government to support, implying that the government may consider underwriting risks to lower capital costs for investors and, hence, lower support costs per unit of H2 (e.g., by 12-17% for AEC if its WACC is reduced from 9% to 2%).

In the foreseeable future, there is little chance of putting a price on carbon emissions in the US. Instead, the IRA framework offers unprecedented financial incentives to stimulate private capital into low-carbon energy technologies. On the contrary, the EU’s flagship carbon pricing is regarded as the first-best economic policy to tackle carbon emissions (Bennear & Stavins, 2007; Klenert et al., 2018; Nordhaus, 1992). Perhaps not by design, the interactions between the CBAM and IRA will likely mean stronger incentives to decarbonize US AP than standalone IRA. The relatively small carbon taxing and the opportunity to trade CBAM certificates could substantially increase the relative economics of US-based LCAP: grid connection (Scenario A) is now a cost-effective option for at least CCS and BH2S. Under CBAM and IRA, the CAC to decarbonize US AP via CCS and BH2S could be much lower, falling in the recent range of EU carbon prices. This finding reconfirms the potential effectiveness of multiple policy instruments in a “second-best” world (Bennear & Stavins, 2007; Lehmann, 2012; Sorrell, 2003) to reduce the US AP carbon emissions.

There is considerable debate about consequential emissions from renewable electricity and hydrogen production matching rules. Starting from the monthly matching rule will not unduly penalize AEC’s economics while ensuring lower consequential emissions than the yearly rule. While the hourly matching rule ensures limited consequential emissions from the AEC, its unfavorable economics will unlikely stimulate private investment. Hourly-matched AEC pathway seems unlikely a worthwhile avenue to pursue from the public policy perspective because its support cost outweighs the carbon savings benefits (in most cases, AEC’s CAC is substantially higher than the social cost of carbon).

AP is expected to almost triple (688 Mt/year) by 2050, with 83% from renewable ammonia (IRENA, 2022). If renewable ammonia is part of this vision, then advancements in the flexibility of the HB process are a crucial avenue for research and development. Some research has highlighted the challenges of flexible HB. The literature reports HB may handle wide ranges of output (5-80% of capacity) and ramping rates (20% capacity/hour) based on feasibility studies and industry opinion (Armijo & Philibert, 2020; Lazouski et al., 2022; Verleysen et al., 2023). However, the demonstration of flexible HB on a small scale only starts, while the additional costs of flexible HB loops on a commercial scale are unclear. Given the current industry state versus the optimistic techno-economic literature, it may be a reality that flexible HB may exist commercially in the next ten years but beyond the IRA timeline. Nevertheless, the incentives for making flexible HB are clear under an electric grid with increasingly fluctuating renewables: our results highlight that the economic benefit of flexible HB could be substantial: $3.4-7.4 bn or $96-207/tNH3.

Thus, to decarbonize AP in the US cost-efficiently, there are key areas for policymakers and the academic community to focus on in the next decade: (i) adapting HB to variable bioenergy quality and process efficiency while ensuring feedstock’s sustainability and availability (ii) ensuring safe transport and permanent storage of CO2 while de-risking CCS value chain, (iii) supporting research and development to drive down cost and efficiency improvements of flexible HB, renewable energy, and electrical and hydrogen-based storage, (iv) policy support framework should ensure technology neutrality and competition while recognizing the nature of “dynamic” technology cost reduction (Gillingham & Stock, 2018) and interactions between policy instruments and between technologies.